Marc taught me to re-arrange furniture, Stuart taught me to smash it up*

Kathy NobleWritten to accompany Terra Conductor: Judith Goddard

Installation view, Terra Conductor: Judith Goddard, Chandelier Projects

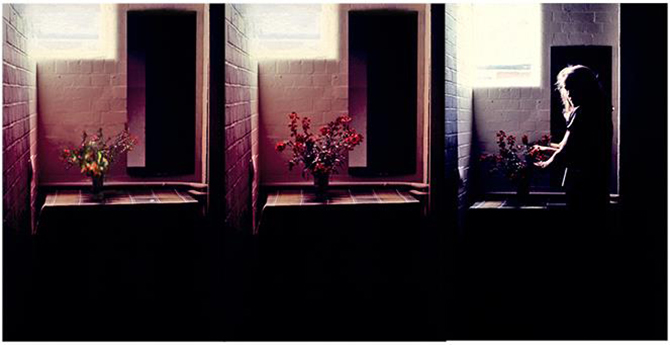

Judith Goddard describes Wallflower Triptych (1979) as a work that contains elements of everything that she has thought about and made since. The work comprises three versions of the same scene. A table sits underneath a mirror, hung next to the corner of a window. On it sits a vase of wallflowers, petals shrivelled, wilting over the sides of the vase. Projected to the right of this real mis-en-scene is a still image of the table, vase, flowers and mirror – yet in this scene, the flowers are pert and fresh. Projected, again, to the right of the still image is a 16mm film of Goddard arranging the flowers when they were fresh to make the installation. As such, the flowers began their decomposition during their time in the ‘live’ element of this artwork, becoming a kind of memento mori; however their smell infused the space, as a reminder of their life.

Judith Goddard, Wallflower Triptych, 1979

The third moving image in this triptych is also the first, in that the others could not exist without Goddard’s initial act of arranging. The second still image functions to immortalise the act performed by Goddard. The first image, the ‘live’ scene – a highly staged tableaux, akin to both a landscape and a still life – is both the first and the last act, where the objects are both sculptures and props. The mirror reflects the viewer, creating a situation in which they are watching themselves watching – as if the mirror is the eye of the artist. Wallflower functions in an infinite cycle, as if a video on a loop; as the making of the work is the work, the viewer is the work, the artist is the work and the work is the work. Each stage in the triptych – live and performed, filmed, photographed and the staged objects – are inextricable from one another, as they are mediated via a series of different technologies, posing a challenge to what might be ‘authentic’ and what might be ‘artifice’ and whether one ever exists without the other. This cycle or loop of different iterations and repetitions of a live situation, was extremely prescient, as a predecessor to the way we perform our lives online today; the staging of life, and the viewing and being viewed inherent in this, is an idea that reoccurs repeatedly in Goddard’s work, revealing the friction between authenticity and artifice.

Goddard studied art at Reading University where she was taught by the artists Marc Camille Chaimowicz and Stuart Brisley. Although both artists work with performance and installation, their work differs drastically in terms of aesthetic, conceptual and formal concerns in that Chaimowicz creates beautifully stylised interiors and fictional scenes, whilst Brisley creats brutal, visceral works in which he violently transforms his body and the space he is in, using paint and other materials. These almost contradictory approaches were very influential in the formation of Goddard’s own investigation of how the psychological and the material meet.

This addressing of space, experience, aesthetics and destruction, and the manifestation of the interior via material and action, occurs repeatedly in later works by Goddard – such as the video You may break (1983), which captures Goddard repeatedly arranging and then smashing a vase of roses on a table, accompanied by a noise akin to a bomb explosion, followed by its echoes. The first version is so saturated with light, that the act is highly abstracted; small flickers of psychedelic colour flit around, breaking through the white surface, and with each repetition, the scene’s definition moves further towards reality, as the vase and hand are clarified. After the fourth smash, the soundtrack continues as the video moves through images of gloopy, pinky-orange visceral colours, as if inside a body. The initial abstraction via technology, combined with the repetition of the act, to reveal its reality, aestheticises this staged act of violence – it is really only the sound that conveys the gravity of destruction.

In the same year, Goddard made the film Lyrical Doubt, the last of her works in which she performed herself. The image is comprised of two scenes, presented spliced together in a wonky diagonal that fractures the screen – the foreground, which mostly depicts Goddard sitting in a Wicker chair, and the background shot on Super 8, depicting varied imagery of flowers. Her face is half missing, as the Super 8 film roughly obliterates her left hand side, as if the film is her interior thoughts flowing out. It is accompanied by ominous synth music composed by Peter Culshaw, which later merges into a full choir rendition of J. S. Bach’s St John’s Passion. The split screen vision of Goddard is interspersed with other scenes, including various clock towers and hands squeezing gooey food in front of a video of a baby. Lyrical Doubt conveys an abstract series of metaphors and associations, but again explores how one’s interior psychology might have an outward material manifestation. Alongside this, the collaging of different mediums, the smashed or fractured screen, the use of music in something that feels akin to 80s pop videos, were pioneering acts at the time they were made.

Since the late 80s Goddard has created numerous works incorporating video, sound, light and sculpture – such as The Garden of Earthly Delights (1991), Descry (1992) and Helen’s Room (1995 – 2005) at Kettle’s Yard (1992), Myrrha (2001) and Mirador (2004). However, the questions posed in her early works – the exterior performance of interior psychology and its relationship to materiality, and its inevitable destruction – continue to provoke new ideas and are extremely prescient to her most recent work displayed in the exhibition Terra Conductor.

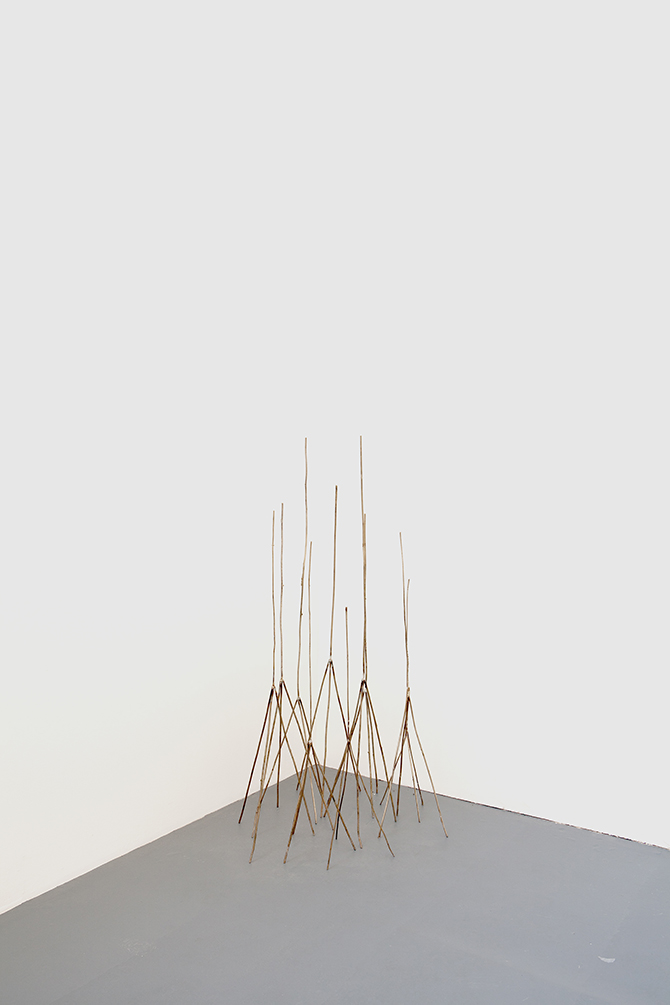

Installation view, Terra Conductor: Judith Goddard, Chandelier Projects

Terra Conductors (2014) comprises one large and many small bronze tri-legged structures, a few of which stand as markers in the space, the rest a collection in a corner at the back of the room. They appear as insect-like animals – perhaps the post-apocalyptic descendant of the spider family – and exude vulnerability, as although the spindly lengths are firmly welded together, they seem to struggle to stand up. They also resemble the tripartite nature of 19th century lightening conductors, which conduct electrical energy to earth – hence the title of the work. However, if one reads ‘terra’ as ‘terror’ the sculptures take on another layer of meaning, as a metaphor for the conduction or transmission of psychological terror, via a material object. Presented alongside these are the series Bronze Photograms (2014) created using the sculptures to project light onto photographic paper, quite literally using them to conduct energy – yet rather than destruction, a glowing streak of white light is formed, loosely in the shape of the sculpture, on the blackest of black backgrounds.

These are displayed alongside two more bronze sculptures which resemble slightly abstracted, or collapsing skyscrapers. Given the context of ‘terra’ and ‘terror’, alongside their girder-like aesthetic, I can not help but think of the Twin Towers and their collapse during the terrorist attack in New York on September 11th 2001, which leads to the idea of the psychology of terror being transmitted via the body of an object to the ground – an object that is destroyed by this transmission. Strangely, and presciently, in 1985, Goddard made the video Celestial Light and Monstrous Races, in which a plane appears to disappear into a building.

The video Wrap (2014) also explores the idea of the transmission of energy to an object, inanimate, or dead thing, as a spider is depicted repeatedly looping a cocoon of silk around a dead hornet. The video is an extreme close up in which every detail can be seen – as if the web is an intricate theatre set, in which he/she performs the ritual of wrapping the dead, in order to consume it, and in turn, to produce energy for its own life. A second video Lowest Point, Kati Thandi (Belt Bay) (2014) was shot at the lowest point in Australia, on the planes of a dry salt lake, the earth dry and barren from lack of water, with a mirage of a lake appearing in the distance, forming a scene in which real and artifice exist at once in the natural world – serving to emphasise how artificial, or imaginary, the idea of authentic, or real, actually might be.

Each of these works is cyclical, existing in a loop between reality, performance and artifice, and also life and death, in the same way the early work Wallflower did. And each considers the relationship between the transmission of energy physically and psychologically via material. However, this series of works exudes a sense of fragility and vulnerability not present in Goddard’s early videos. In the exhibition Terra Conductor nothing is solid: here the sturdiest, long-lasting of materials – bronze – is a fragile, failing entity in Goddard’s sculpture, only just able to hold its form, existing as if on the verge of collapse. The inference of ‘terror’ from ‘terra’, also links back to Goddard’s consideration of destruction in earlier works. Today, real-life acts of terror are quite literally staged and broadcast publicly for the world to consume on a screen – this mediatisation, or transmission of an action, and the psychological energy conducted through a material, underpins all the work in Terra Conductor and also informs Goddard’s overall concerns as an artist.

* Judith Goddard, in conversation with Kathy Noble in Goddard’s studio, August 2014